|

Link:

Ethics

in Emergency Medicine, 2nd ed. Ethics

in Emergency Medicine, 2nd ed.

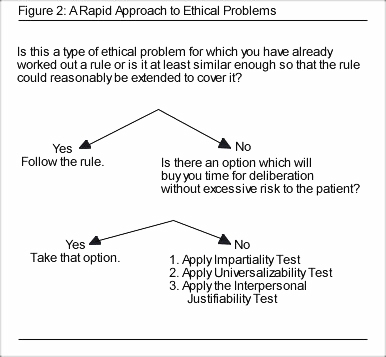

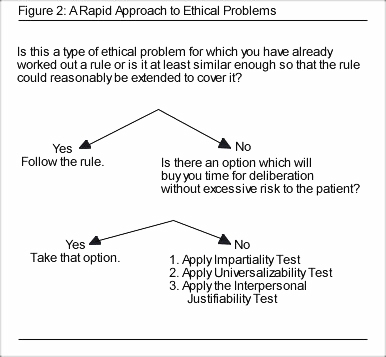

A

Rapid Approach to Ethical Problems

From: Ethics In Emergency Medicine, Second Edition

Iserson

KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D (Editors)

ISBN

1-883620-14-7

$39.95 Soft Cover

589 pages, Bibliography, index

©Galen Press, Ltd., Tucson, AZ, 1995

The

Impartiality Test

Would

you be willing to have this action performed if you were in the

other person's (the patient's) place? This is, in essence, a version

of the Golden Rule. Do unto others as you would have done unto you.

According to John Stuart Mill, this espouses "the complete

spirit of the ethics of utility." It is not an infallible rule

that will yield a right answer every time. It is intended, however,

to correct for one obvious source of moral error-partiality, or

self-interested bias. It asks practitioners to switch their point

of view, to take the other person's perspective. Usually, that is

useful to do and can at least help avoid a grievous error.

The

Universalizability Test

Are you willing

to have this action performed in all relevantly similar circumstances?

This generalizes the action and asks whether developing a universal

rule for the contemplated behavior is reasonable-an application

of Kant's categorical imperative. Is what you are about to do in

this particular case something you would approve of if it were generalized

to all cases of this sort? The usefulness of this test is that it

can help eliminate not only bias and partiality, but also shortsightedness.

In particular, it enables us to evaluate a particular action by

viewing it as an example of general practice in relevantly similar

circumstances. In some cases, we might approve of a particular action

if we viewed it on its own account, in complete isolation, but find

it unacceptable to adopt it as general practice. To the extent that

we are concerned with finding useful rules of action, focusing on

types of action-rather than particular actions in isolation-seems

appropriate, since rules are always to some extent general and hence

apply to types of actions. Justifying one particular instance that

falls under a rule is not sufficient for justifying the practice

of acting on that rule.

The

Interpersonal Justifiability Test

Are you able

to provide good reasons to justify your actions to others? Will

peers, superiors, or the public be satisfied with the answers? Could

you justify or defend your decision if it were questioned by someone

else? Could you give reasons for the course of action you took?

And, importantly, can you give reasons that you would be willing

to state publicly? This test uses David Gauthier's basic theory

of consensus values as a

final screen for a proposed action.

When ethical situations arise where no time exists for further deliberation,

it is probably best to go ahead and act on the rule or perform the

action that allows all three tests to be answered in the affirmative

with some degree of confidence. Once the crisis has subsided, however,

the practitioner should review the decision with the aid of colleagues

and bioethicists to refine his emergency ethical decision-making

abilities. In particular, it is crucial to ask whether the most

basic ethical values have been served by the decision-making process.

Were the actions taken in the emergency situation really consonant

with showing the kind of respect for patient autonomy which you

believe appropriate? Were the ethical decisions really in the patient's

best interest, or were you unduly influenced by the interests of

others or considerations of your own convenience or psychological

comfort? Were people treated fairly, justly, and equitably?

Ethical

problems, like emergency clinical problems, require action for resolution.

Ideally, one would have extensive discussions and time to reflect

on each ethical decision before needing to act on the decision.

This, of course, is not possible for many emergency care decisions.

Nevertheless, by making a sincere effort to anticipate recurring

types of problems, by subjecting them to ethical analysis in advance,

and by conscientiously reviewing decisions after they have been

made, the emergency care professional can better fulfill his or

her ethical responsibilities. The fact that a decision is an emergency

decision, therefore, does not remove it from the realm of ethical

evaluation.

|

EXTRAS

EXTRAS

Ethics

in Emergency Medicine, 2nd ed.

Ethics

in Emergency Medicine, 2nd ed.